Saturday morning (May 31, 2014) I woke early with a feeling of joy and excitement. Several hundred miles away from me, a group of eight men and women were in New York City, getting ready for their session at Book Con 2014 (BookCon is part of Book Expo America, BEA for short). The weeks, days, and hours prior to their session were--for me--a roller coaster of highs and lows. I cannot imagine what it was like for them. What follows is the story of We Need Diverse Books as I experienced it. It is my thank you and shout out to a group that sparked a moment and movement that may mark the turning point in the all white world of children's books...

In April, two things happened. BEA announced a panel of blockbuster kidlit writers. That panel was composed of four men and a cat. And, BookCon announced its line-up of authors. This "

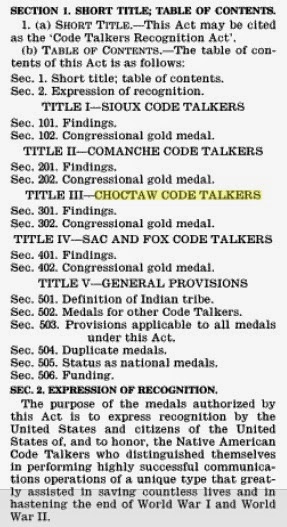

blindingly white" situation prompted indignation amongst a lot of people. A group was formed. That group is We Need Diverse Books. Their goal was/is to promote books that showcase and promote diversity of content, and diversity of authors that create that content. On May 28th,

Aisha Saeed wrote about the upcoming trip to NYC.

I followed the campaign when it was launched in late April, offering help as I could behind-the-scenes, but mostly I used social media to promote the

We Need Diverse Books campaign. This is the first graphic the WNDB team released:

Gorgeous, isn't it? The energy radiating from the team was inspiring. With twitter driving it, the campaign took off around the world. Media covered it. The result? BookCon invited the team to do a session in NYC on Saturday morning.

On the 29th (Thursday), I made a graphic with the WNDB logo and location info for their session. I started to tweet it:

On Friday morning (May 30), excitement was building.

Ilene Wong of the WNDB team sent this tweet:

My excitement grew when I saw tweets of photos of large displays announcing the location of the WNDB session:

That excitement was tamped down a bit as I read tweets from Cheryl Willis Hudson of

Just Us Books. She was walking through the exhibit halls at BEA, looking for books within the diverse framework. She didn't see much, but did take photos and sent them out. Aren't they terrific? Here's her photo of

Because They Marched at the Holiday House booth:

And here's a photo she snapped of Jacqueline Woodson signing books. See what Cheryl said? "Long line" --- cool!

Here's more photos Cheryl sent out:

As I read tweets from Cheryl and those in the We Need Diverse Books hashtag on twitter, I saw that Cinco Punto Press had tweeted a photo of Tim Tingle's

House of Purple Cedar. It was there, on their table, at BEA. I retweeted their photo:

There were to be two other sessions at BEA that focused on diversity. I tweeted info on them, too. One was "Multicultural Publishers in Conversation." Here's that flyer. As you can see,

Just Us Books and

Cinco Punto Press were scheduled for that conversation on Saturday at 12:45.

Here's the flyer for the third session, "Where Are the People of Color in Children's Books?":

But look! See the time slot in the red bar at top of the graphic? Saturday, 10:00 AM... The same time as the We Need Diverse Books session! I was stomping mad about that, with various obscenities whirling in my head. Then I saw this set of tweets by Ellen Oh (retweeted by Ilene Wong):

What obstacles, I wondered? I figured one was the overlap of the WNDB session and the conversation with publishers session, but Ellen said "obstacles" (plural), so what else went wrong?! Lights out for me... I went to bed.

Early Saturday morning I was up and catching up on tweets from the night. I learned that the hard copy of the conference program did not have the WNDB session in it.

People at the Javits were sending out tweets and photos:

And

Jacqueline Woodson snapped a

way-cool photo of Matt de la Pena arriving at her house. They were going to head over to the Javits center together.

As 10:00 AM drew near, the #WeNeedDiverseBooks tweets from the conference were growing in number.

I saw that the WNDB team had created swag!

And panelist

Grace Lin had a "cheat sheet" handout with ways that booksellers can hand-sell books to consumers who shy away from books by or about people of color (get the

pdf from her blog):

I wondered how big the room was but when the first photos of the room (as it filled up) started to come across twitter, I estimated 200 chairs. This photo was taken by Ilene Wong, as she notes, 35 minutes before the panel started.

And...

And of course, people in the audience were taking/tweeting LOTS of photos of the panelists:

The room itself filled up and people were turned away (media reports later said there were 300 people in the room, with people in the aisles and three-deep along the back wall). Meanwhile, in the room, the panelists received a terrific reception from the audience:

Panelists delivered powerful remarks that were tweeted and retweeted. Again and again I wished I was in that room rather than hundreds of miles away. I was glad to see tweets indicating that

Matt de la Pena had a few things to say about the shut down of the Mexican American Studies program in Tucson Unified School district. Over and over, I was glad for twitter. The emotion captured in photos was astounding.

An

unedited audio of the session is now available at the We Need Diverse Books tumblr. No doubt the panelists and WNDB team was bursting with joy once the session ended. Marieke Nijkamp's tweet captures some of their emotion:

I was especially moved by

Mike Jung's tweets as he left the conference:

It was VERY poor planning on the part of BEA to offer WNDB and the "Where are the People of Color" session at the same time. I assume it and the "Multicultural Publishers in Conversation" session were both in the program.

A curious thing, though, was the floor announcement, as captured in this photo tweeted by

Daniel Jose Older (photo taken by

Tiffany D. Jackson). See the title for the session? How small it is in comparison to the titles of other sessions? And doesn't it look like it was pasted on there? Why?!

Of course, Daniel's jab ("Diversity is so awesome!!!!) is directed at conference planners, and not diversity itself. I don't know if he made it to the 12:45 session. Cheryl Willis Hudson was there and tweeted some photos. Here's one:

Today (June 2, 2014), several recaps of BEA were loaded online. I especially liked what

Lyn Miller Lachmann said in her piece, and what

Allie Bruce said in hers. Both are committed to diversity, and their commitment shows in their writing. I loved hearing the voices of

Ellen Oh,

Lamar Giles, and

Jacqueline Woodson in their

interview with NPR. Claire Kirch's recap for Publishers Weekly is

here. Among the things you'll read is that WNDB is working with the National Education Association, and that Lee and Low is launching a "

New Visions Award." The big news? That a book festival is being planned...

A good many people have been pushing for diversity for a very long time. With respect to Native people objecting, I think back to William Apes, a Pequot man who was raised by a white family for a portion of his childhood. He read the books they gave him, and because of what he read, was afraid of Indians! He wrote about that fear as an adult, in his

Son of the Forest, published in 1831.

In June of 2014, it feels like some substantial change will take hold because the demographics in the country are shifting dramatically. I am optimistic. And--I look forward to meeting members of

the WNDB team in Washington DC in 2016 at a festival of diversity in children's books! The plans are in the works. Till then, AICL stands with We Need Diverse Books. This is a cheesy closure but I'll use it anyway... STAY TUNED.

A special note of thanks to Cheryl Willis Hudson of Just Us Books for all that she shared from BEA. I know from 20 years of reviewing children's books that small independent publishers are more likely than the big publishing houses to give us wonderful books that accurately reflect the lives of people of color. For that reason, I've been standing with small publishers for a long time. They embody a commitment to truth over profit.

.jpg)